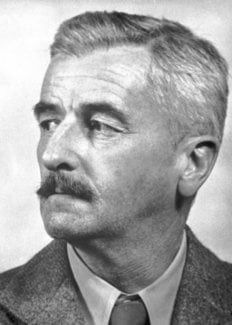

William Faulkner emerged as a budding poetic talent while in high school, writing in a style derivative of Robert Burns, Swinburne and A. E. Housman. He left high school before graduating, and by the time he published his first novel in 1926.

In 1924, with the help of his friend and literary mentor Phil Stone, Faulkner published a volume of poetry The Marble Faun. His first novel Soldiers’ Pay was written in the following year and published in 1926. Based partially on his brief experience in the RAF, it was about the homecoming of a fatally wounded aviator.

After a

brief tour of Europe and the publication of a second novel, Mosquitoes (1927).

Faulkner decided to write more about his native region and to use the local

lore and family tales that he had absorbed during his childhood and

adolescence. He fictionalised the region under the invented name ‘Yoknapatawapha

County’ drawing on both regional geography and his family

history, particularly his great-grandfather's military exploits. The first

novel to explore this setting was Sartoris (1929), and from then on few of his

works were set outside Yoknapatawpha.

Faulkner's

next novel, The Sound and the Fury (1929), shows the emergence of themes that

would recur throughout his fiction. Through the account of the slow decline of

a prominent family, the novel explores the decadence of the American South

after the Civil War, and the slow dissolution of traditional values and

authority. The technical innovation displayed in the novel shows the influence

of Modernist writers (Faulkner was a great admirer of James Joyce). The four parts

of the novel are narrated by three brothers, and an idiot who has a weak grasp

of the concept of time. This allows Faulkner to employ a range of styles, and

freely move the narrative back and forth between past and present.

Faulkner

had written another novel, Sanctuary, earlier in 1929, but had to wait until

1931 before it was published in a heavily revised form, because of its

controversial subject matter. Dealing with the abduction and rape of a young

woman, Sanctuary attempts to portray the sordidness and violence which he saw

as features of the South's moral degeneration. His professed reason for writing

it was to make money, and indeed Sanctuary remained his best-selling book for a

long time.

The

technical experimentation of The Sound and the Fury was taken farther in ‘As I Lay

Dying’ (1930), a tour de force which Faulkner claimed to have written in six

weeks, without changing a word. The novel deals with the death of a matriarch

in a poor Southern family, and her wish to be buried in Jefferson, ‘a hard

day's ride away’ to the north. The narrative consists of the streams of

consciousness of 15 characters, organised into 59 chapters, describing the death and the family's subsequent

journey with the body.

Faulkner

seems to have wanted to write a novel called Dark House, and his manuscripts

bear evidence that he started writing it at least twice. The first attempt

introduced the theme of racial difference, which gained prominence in his later

works. Through the depiction of Joe Christmas, an orphan of uncertain racial

origin, Lena Grove, a pregnant girl who is on a quest to find her child's

father, and other marginalised characters of Yoknapatawpha, Faulkner produced a

tightly structured tale which was published in 1932 as Light in August.

The

second manuscript which Faulkner originally called Dark House became an enormously

complex and self-conscious narrative in which four principal narrators (one of

them being Quentin Compson who is also one of the narrators in The Sound and

the Fury) try to put together pieces of evidence in their reconstruction of the

mystery behind the life and death of the demonic Thomast Sutpen, killed more

than 40 years earlier. The novel, finally called Absalom, Absalom! (1936), can

be read as addressing problems of textuality and reading strategy, an

exploration of how meaning is created through interpretation.

He wrote the

screenplays for Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not and Raymond Chandler's

The Big Sleep, and collaborated with Jean Renoir on the latter's ‘The

Southerner’.

The

publication of Go Down, Moses in 1942 is sometimes regarded as marking the end

of Faulkner's so-called ‘great decade’ of writing. Faulkner insisted that Go

Down, Moses was a novel, although it consisted of

several short stories, many of them previously published, involving diverse

characters spanning a century in the history of Yoknapatawpha County. At the

centre of the book is the story 'The Bear', arguably Faulkner's best-known

short work. His later works are generally considered to be weak, although

Faulkner himself regarded A Fable (1954), an intricate symbolic narrative about

a reincarnation of Christ during a French soldiers' mutiny in the trenches of

the First World War, that took him more than ten years to complete, to be his

masterpiece. Along with Pylon (1935) and The Wild Palms (1939), it was also one

of the few mature works by him that did not have Yoknapatawpha County as their

setting.

Among his

later works is the so-called 'Snopes Trilogy', consisting of The Hamlet (1940).

The Town (1957) and The Mansion (1959). The trilogy portrays the ruthless rise

to power of a new 'redneck' middle class in the South, embodied in the

character of the avaricious and ambitious Flem Snopes, which had little regard

for tradition. Requiem for a Nun (1951), a semi-dramatic sequel to Sanctuary

written in collaboration with Joan Williams, earned the distinction of being

adapted for the stage by Albert Camus in 1956.

Faulkner

was awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature, and became an increasingly

public figure, being chosen by the US State Department as a cultural ambassador

and asked to undertake goodwill tours abroad. As well as several other awards

and medals, Faulkner received the Pulitzer Prize for Literature twice.

No comments:

Post a Comment

looking forward your feedbacks in the comment box.